Your Superfund - Voronoi Tesselations

This Your Superfund project is testing out a new trick - doing nearest-neighbor queries with UTFGrid. The homepage ‘your superfund’ dialog is powered by a tileset - specifically this tileset. There’s no additional magic or computation, so it can figure out your superfund really quickly, and here’s how.

It’s possible to find the nearest ‘thing’ to any place in constant time, by pre-calculating results and using a Voronoi tesselation. This is part two of my post on point-in-polygon searches with UTFGrid, and a whole level of it is precisely the same thing.

This is, again, taking advantage of the fact that UTFGrid lets you do point-in-polygon searches by proxy - doing point-in-raster searches, with grid tiles as the intermediary. Since we can use all of the heavy equipment made for mapmaking with TileMill and such, we can store millions of tiles and make this heuristic gradually more precise - at zoom level 18, you’ll only have 2.4 meters potential for error. Since data input is often geocoded points which you want to reverse-geocode, or accurate-enough iPhone AGPS, this is typically good enough.

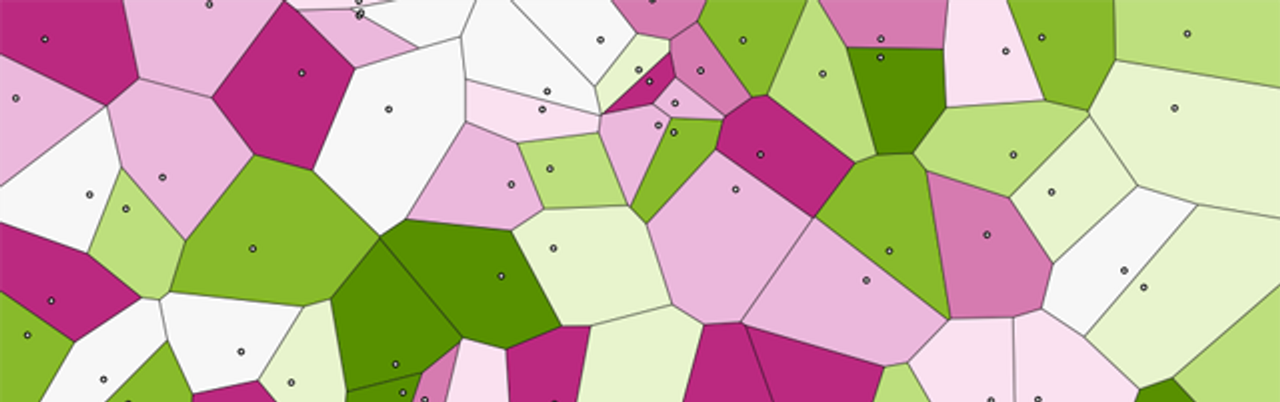

Voronoi diagrams have been used for quite a while in restricted forms, but were generalized and studied by awesomely bearded Georgy Voronoi. (photo via Wikipedia) They’re incredibly clever - essentially a representation of all the places in a space that are nearest to all given points. So, if you land in a polygon (in a ‘site’), you’re closest to the point that the polygon represents - the ‘node.’

Voronoi diagrams have been used for quite a while in restricted forms, but were generalized and studied by awesomely bearded Georgy Voronoi. (photo via Wikipedia) They’re incredibly clever - essentially a representation of all the places in a space that are nearest to all given points. So, if you land in a polygon (in a ‘site’), you’re closest to the point that the polygon represents - the ‘node.’

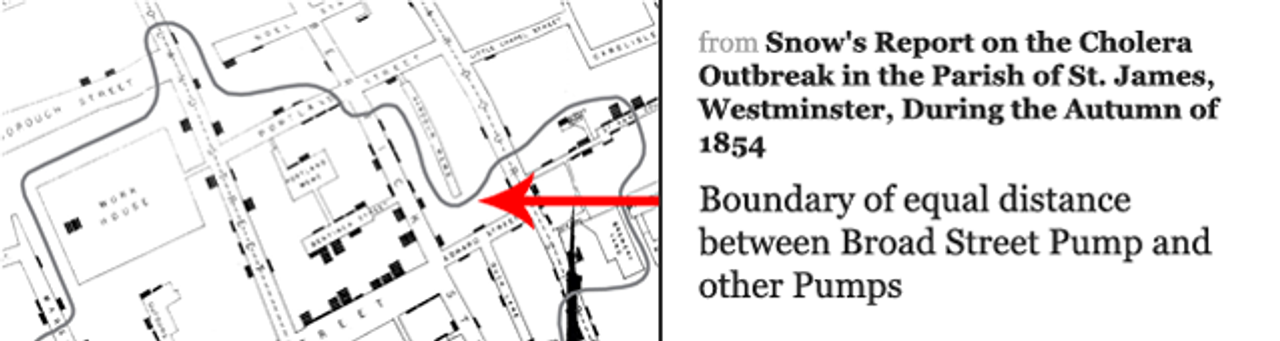

John Snow’s famous-to-a-fault Cholera map, with a Voronoi polygon, though not mathematical/bird of flight, but based on travel distance. More like a isochrome map

Implementing Voronoi tesselations is not easy, nor easy to understand. At this point I only understand it on a conceptual level, mostly thanks to this wonderful essay by David Austin

that describes Fortune’s Algorithm. Basically, it’s an O(n log n) algorithm that interestingly uses events and queues internally to keep track of state. David does a much better job explaining the actual math.

As with any brain-crunchingly hard concept, this is already implemented in d3.js. Even there, the implementation is adapted from a previous version by Nicolas Garcia Belmonte. The d3 implementation is written so that it’s fast on updates so you can run it in-browser and it looks awesome.

Incredibly awesome implementation of Voronoi tesselations in d3

In order to use this in a more general (or, TileMill-friendly) sense, you’ll need data to come along - which isn’t too hard, because the d3 implementation keeps polygons in the same order as it took in nodes. So, I can just pull data from before, and add some wrappers for it to talk GeoJSON, and there we are - the same algorithm (none of the implementation pain), but a much different use case.

Let’s take a quick minute to go over what’s happening here - this is trading one problem space, actual nearest-neighbor search for another, point-in-raster search. So there are catches.

- Voronoi tesselations tell you the nearest point, and only that point. Not a nice list of nearest points, just one.

- This implementation tells you nearest points by bird-of-flight, not travel time, like in John Snow’s map.

- The accuracy of this method is limited by raster resolution: more precomputation (more tiles rendered at higher zoom levels) means higher accuracy, but there’s no mathematical promise here.

But, like the UTFGrid query example, this flips around the problem space in a pretty cool way:

- There’s virtually no computation involved in finding a result. Call it

O(n), or ‘download time’, but things can be blazingly fast. - There are no special servers online. I’m using MapBox Hosting, but you could have your data sitting in files, if you want to manage millions of files. I’m biased, but I’d say you don’t want to do that. All the host is doing is sending you a tiled data file, something that it can do near-instantly.

- This is relatively easy. The algorithm’s generalized, you can send whatever point data you want at it, and it’ll ‘just work.’ Instead of building a ‘thing finder’ in a week, you can do one in an afternoon and not freak out about keeping it online.

- Computing Voronoi grids is decently fast - the d3 code running in node.js computed these 1.6k points in 320 milliseconds. The render took about 20 minutes to zoom level 11 - consult the graph in the old UTFGridQuery post for some real numbers as far as accuracy.

That’s all for now - I’m planning a bit more on the site about Superfund sites and a follow-up post on the domain.