d3 for HTML

- React has taken the world by storm and achieves the same goals outlined in this post, in a way that's simpler to write (for HTML), at the cost of less naturally expressed transitions and animations.

- I'm now working at Observable with Mike Bostock, the author of d3.

On Friday, I'm doing a quick presentation about the process of building iD in d3. This is a preformation of thought aimed at reducing onstage wandering and equalizing what I say for those who won't be there for any reason.

And so, d3 for HTML.

d3 is a JavaScript library that has the stated aim of ‘manipulating documents based on data’. In its rise to prominence, d3 became known mainly in combination with SVG - the recipe that yields pretty streamgraphs and maps, and the one for which much of the library is built. The gallery is beautiful - the internet’s top design/coders use d3 to build incredible things.

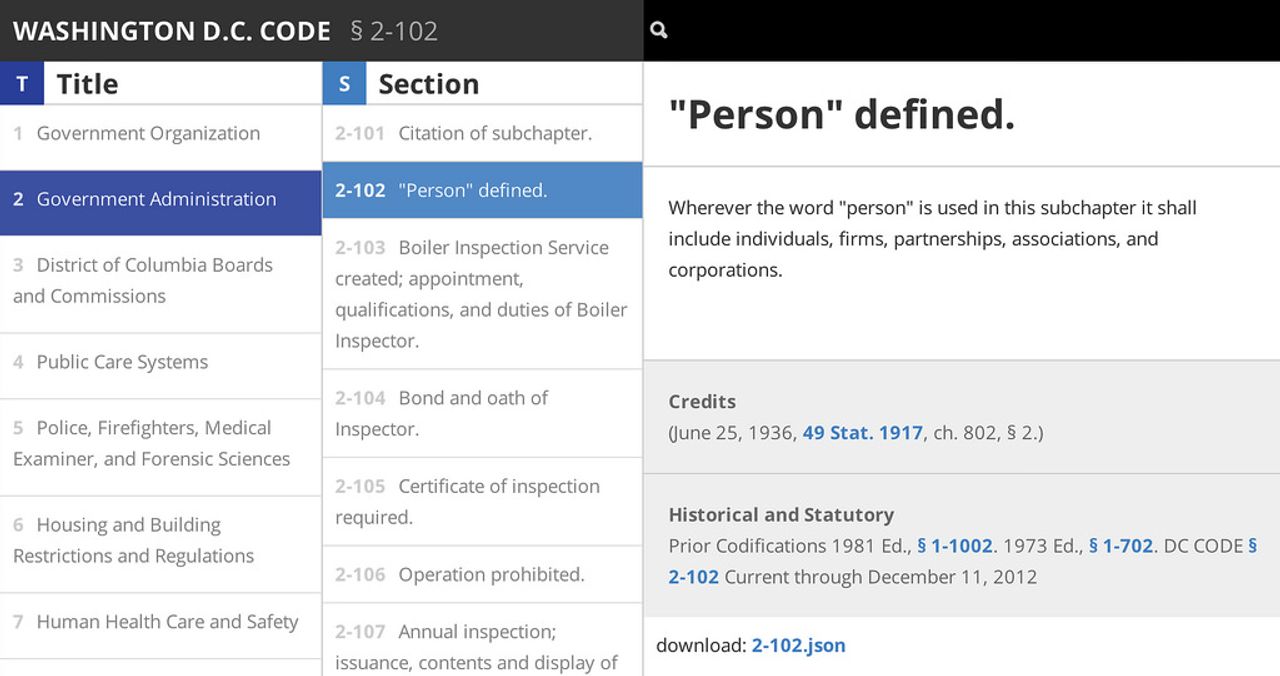

And then I built dccode.org/browser in all ‘pure’ d3.1 It doesn’t touch d3’s incredible ability to build interactive maps or beautiful graphs like you’ll see in infinite scroll of Mike’s bl.ocks.org page. In fact it’s pretty boring from a technical perspective, as a flat website that’s just HTML, with permalinks and the classic multiple-column navigation pattern.

Here’s a bit on why we shoehorned a ‘visualization framework’ into the boring old law. For reference, the GitHub repository so you can see the code.

Data

d3.json('index.json').on('load', function(index) {

titles_div.datum(index.titles)

// and so on.

});d3’s idea of data is extremely flexible. There’s no idea of a ‘Model’ in the conventional sense - instead the data bound to the document is simply anything that’s a list of objects. This comes in handy in cases where data is simple and flat, like the browser.

It also helps in way more complicated cases like in the iD editor, in which the model is not only a persistent object graph like Git, but the application also needs to compensate for missing data and heavily validate each state.

Templates / No Templates / The View

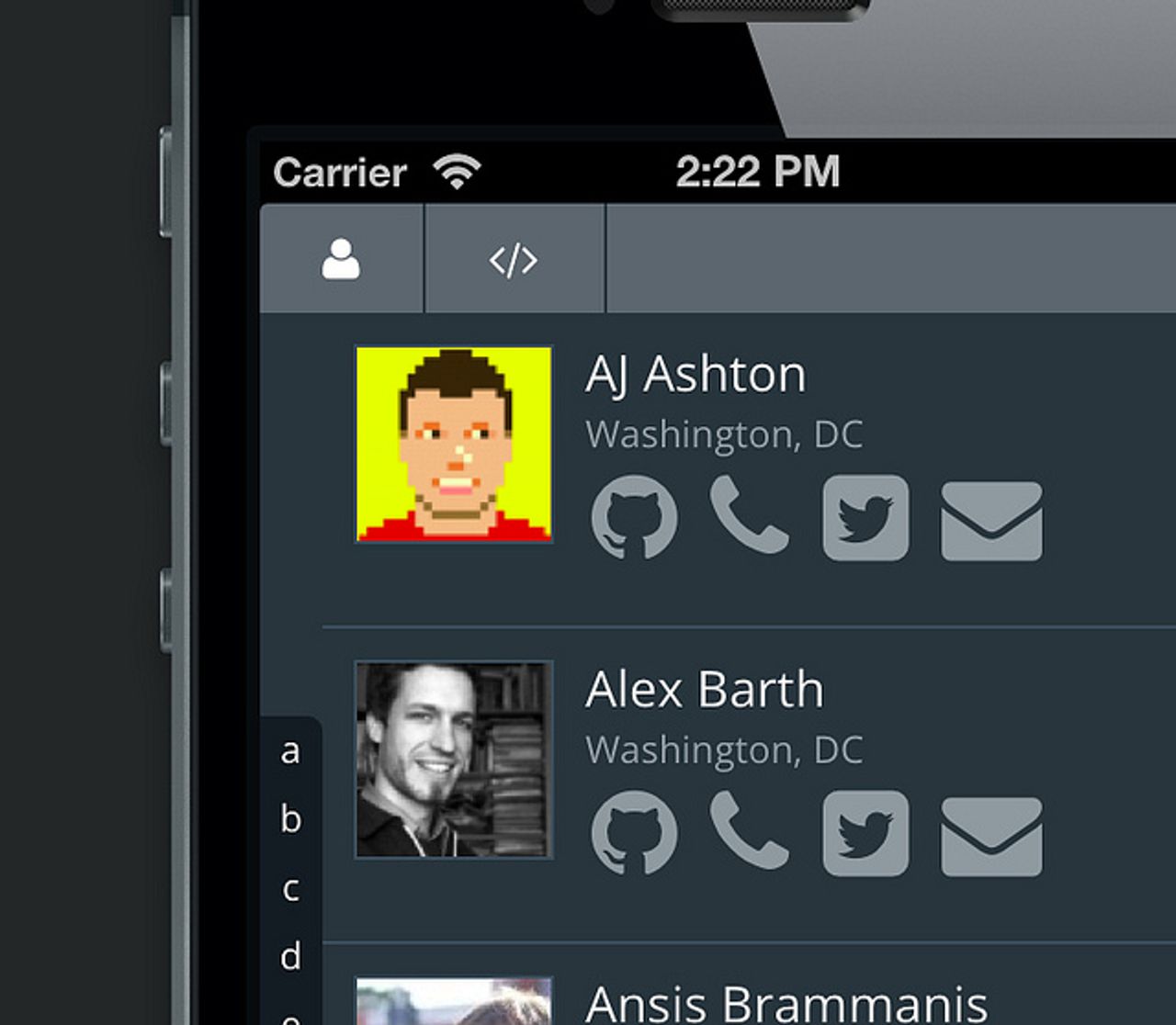

One recent project was building an intranet for MapBox - a bare minimum ‘who we are and what we are saying’ type system. So, it’s essentially a handful of small projects that pull from collectively-edited JSON documents and the GitHub API.

Posting about this and giving a quick in-house talk on building those kinds of things with d3 brought up a point I had forgotten about: when you build with d3, you almost never use templating.

This is an interesting bit, because there’s a very valid case against it.

Templates

Templates are an odd thing. In the JavaScript land, templates are basically a hack, though a very popular one. If you look at a popular templating system like underscore’s, the templating code is a collection of things that would make JSHint faint.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that - it’s an effective and contained sort of hack. But the integration of templates into Backbone.js or any other system shouldn’t distract one from the fact that you’re turning strings into code, running that against more code and some data, producing more strings, and then cramming this into a page with innerHTML and hoping it all turns out okay.

Views

So maybe it’s easier to talk about why it’s better to write confusing-looking JavaScript rather than friendly-looking HTML templates when one considers the page as a view rather than a semi-static representation.2

So, in a first iteration of a site, you might build a template that looks like

<% _.each(animals, function(a) { %>

<span class='animal'><%= a.name %></span>

<% }); %>And then in your Bootstrap view, you’ll have a chunk that catches click events on that span and routes those clicks to a certain method.

events: {

"click .animal": "animalClick"

}That animalClick function then gets the event, and does something like

var thisAnimal = $(e.target, this.el).text();To figure out which one was clicked. Until you have multiple animals with the same name, in which case you edit the template to include something like data-id='animalid' - that is, if animals have unique IDs that can be represented as strings in HTML. Then, your click handler pulls from that attribute, and searches through its model to figure out which one was clicked.

In reality, we end up doing a lot of data storage and reference in the DOM, but storage in attributes - in data attributes, in the contents of href, and so on.

Finally, when you modify the DOM, you’re modifying what you created with a template - so you need to make assumptions based on what’s in the template, especially in terms of ‘semantic classes’ like active, which are often used for more than just styling.

With d3

Building views in d3 has a sort of simplicity that comes after accepting the aha-jump of understanding selections and so on. That is, instead of being in a different mode when you’re templating a page, receiving events, and modifying the DOM, it’s all in the same place, without any scary abstractions.

Create a list of 3 elements, for example:

d3.select('body')

.selectAll('div')

.data([1,2,3])

.enter()

.append('div')

.text(String);When you want to bind an event on a click, at the end of the chain it’s just

.on('click', function(d) {

alert(d);

});And the d argument is always the bound data - there’s no hunt through a datastore with an id pulled from a data attribute as a guide. The clicked element is accessible with a simple this, and changes to it are performed in the same way on updates as they are in its creation.

Selections

To look back to the DC Code example - selections are the bread and butter of structure in d3. Across the screen, you’ll see three selections: navigation, subnavigation, and content. Each is managed with a simple selection and assigned different data as the page changes, similar to how a view works.

For instance, when a section of the law is loaded,

var content = section_div.selectAll('div.content')

.data([section], function(d) { return d.heading.identifier; });

content.exit().remove();

var div = content.enter()

.append('div')

.attr('class', 'content')

.property('scrollTop', 0);

div.append('h1')

.attr('class', 'pad2')

.text(function(d) { return d.heading.catch_text; });From here, it’s easy to add little details, like lists of history, subsections, links, and so on.

Issues

There are, of course, issues with this approach.

While you can create wild abstractions within underscore templates, it’s easier for d3-based code to get out of hand. Between d3’s behaviors, use of higher-order functions, and fancy ways to update the DOM, you can build things that are inaccessible to people who are better at design than you.

You also buy in to d3’s rejection of IE9 and prior - something that you can mostly patch together by using aight but isn’t going to be a fun experience.

Finally, it’s less clear to see how one could move computation to the server with this approach - you can run d3 with node.js and build a DOM with jsdom, but it’s not going to be performant, and there’s the open question of how data bindings could ever make sense in that realm.

And So On.

For the things I’ve needed to make recently, d3 works rather well for going from data to a page, to an interactive or self-updating page. Try it out, see if it works for you.

- Of course, with the awesome help of contributors too

- Implied here is that I'm not a huge proponent of gracefully-degrading websites that can degrated to no-JS. I would rather build specific sites for that. </ul>